E-mail : master@koreastudy.or.kr

Tel : 82-54-851-0700

The Advanced Center for Korean

Studies copyright ⓒ2014

Significance of Woodblocks

1. Symbolism of woodblocks

The woodblocks engraved in Korea were largely for the publication of books, and approximately 80 percent of these were collections of works to demonstrate the academic achievements of Confucian scholars.

These collections encompassed a wide range of styles and genres. Poems and similar writings described the writer’s emotions about life. Other writings were more formal and practical, such as written opinions on political affairs. Some collections were devoted to portraying and describing hard facts, while others were intended to strengthen self-worth or praise others. Eulogies and memorial testaments about loved ones were also collected. Miscellaneous writings included daily journals and descriptions of personal experiences.

The contents of these collections reflected the times, revealing the times the authors lived in; their literary sensibilities, the political situation, the author’s biographical information and even their relationships with others.

Publishing these kinds of collections was an individual endeavor, but sometimes, in the hierarchal system of Joseon society, it was regarded as an issue related to clans, communities, local administrations, and even the entire country. As the blood ties, regionalism and school ties of a deceased author were reflected in the publications of their collections, it was used as a method to raise the social status of the author’s clan and maintain class level and status in rural community society. The publication of such collections was conducted by their descendents and disciples for such purposes, and in the process, the author’s studies were passed down to his descendents and disciples. The origin of publishing such collections dates back to the 16th century when Confucian scholars began publishing their genealogies to distinguish the excellence of their clans and academic achievements from others. Thus, the social significance of publishing a collection is obvious.

For the reasons mentioned above, public debate in the rural community played an important role in determining the rationale to publish a collection of works, and during the debate, some sensitive sociopolitical content was revised or deleted during the editing process of the draft, or even after the publication of the collection. Given this situation, many social issues were involved in the publication of the collection itself.

In the meantime, the late Joseon Dynasty experienced vast changes, in contrast to its early days. With the implementation of the “Uniform Land Tax Law (Daedongbeop)” in the 17th century, taxes were paid in cash. Furthermore, the accumulation of wealth by commoners resulted in: widespread rice planting, the cultivation of commercial crops, large-scale farming, wealthy farmers, development of the labor industry, and the advancement of markets and commerce. Based on this accumulated wealth, more commoners rose in status and the term “yuhyangbungi (divergence of Confucian scholars and rural community)” appeared. Those who rose in status were called “sinhyang (new rural aristocrat)”, and they started forming a certain sphere of influence. Later, they colluded with the government using their economic power and formed an axis of the local governing body. In addition to the “guhyang (existing rural aristocrat),” these new aristocrats built a new governing structure linked by the governors of villages, counties and local communities which caused confrontations between the new and existing aristocrats. Consequently, even battles inside the local community broke out to decide who was the leader. The existing nobility tried to maintain its local leadership by moving their base from the local agency to the local academy. However, their influence weakened drastically when King Gojong (r. 1863-1907) ordered the disbanding of local academies; academies which played the role of last resort in forming public opinion among the existing aristocrats. Afterward, the publication of collections of works became a competitiion to strengthen clan organization and to raise their status. Among the existing collections, more than 70 percent were published from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. However, this does not mean that the quality of these collections decreased. When Daewongun, who disbanded the local academies, reversed his ruling, there were movements to restore the academies, and the order of rural communities formed during the Joseon Dynasty was maintained, even during the Japanese occupation and up to the Korean War. Therefore, the public opinion of the rural Confucian scholars seemed to exert its influence on the publication of these collections in woodblocks.

Records, collections of poems, posthumous works, and posthumous collections accounted for a large portion of these publications. These works, due to their less strict publishing processes, are less sophisticated than collections of literary works. However, ‘less sophisticated’ can be interpreted as meaning their contents are preserved as they were, accurately revealing the societal situation when the author was alive. From this perspective, these works have their own academic value as they include more raw historic data than the refined collections of literary works.

In the encyclopedia titled Jibongyuseol (Topical Discourses of Jibong) (1614), its author, Jibong Yi Su-gwang, indicated that Joseon printing changed from woodblocks to moveable wood type after the Japanese invasion of Joseon in 1592 as the war created economic difficulties. However, printing with woodblocks accounted for the total publication output in the Yeongnam area even after the war, regardless of Yi’s comment. Compared to moveable wood type, woodblocks required much more time and costs, in addition to the additional difficulties of preserving the blocks even after publication. If woodblocks were still preferred over moveable wood type despite the difficulties stated above, there must have been a reason to insist on using them.

In reality, between 30 to 200 copies of a collected work were usually published. In the case of the reprinted Collected Works of Toegye, only 11 sets were published in 1843. Accordingly, the number of printed and distributed collections was extremely small. Taking this into account, publication and distribution seemed to have greater meaning in terms of linking the unity of clans and scholars by sharing and preserving their collections. Hence, it is possible to guess that the real intention of publishing these collections was not to spread knowledge but to secure the woodblocks used to print them.

This is directly related to the reason for publishing collection of works using woodblocks and then preserving them. When a collection was printed with moveable wood type, the printing plates were disassembled as soon as the book was published. However, woodblocks could be preserved for a long time and remain as a record of the author’s excellent academic achievement, maintaining his clan’s social status. Furthermore, for citizens of Yeongnam who were excluded from mainstream politics during the late Joseon Dynasty, the ownership of woodblocks was directly linked with their clan status in rural society. Therefore, collections engraved on woodblocks were constantly published regardless of the introduction of new printing techniques. In addition, some people deeply engaged in the publication of collections considered themselves academic successors of the author, even though they were not blood relatives or direct disciples of the author. From this, we can deduce that the social dynamics in rural communities was directly tied to the publication of collections of works, and that carefully preserving the woodblocks in a jangpangak preserved a link to the community.

2. Hidden information in woodblocks

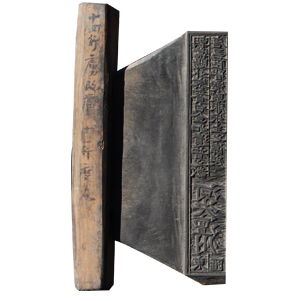

Woodblocks have a variety of information engraved in or written in ink on the end pieces or on their surfaces, which were not actually part of the content of a collection. Generally, the information engraved on end pieces or woodblock surfaces was recorded prior to information that was written in ink, a practice common after the 18th century. This information has quite a lot of content such as the name of the engraver, disciples who participated in publishing the collection of works, the name or official titles of the clan (SongwonhwaDongsaHappyeonGangmok, written by Yi Hang-ro).

The name “Choe Jung-gyeong, engraver”

is written.

A direction of correcting characters in the lines

14 and 18 is written in ink. Songwonhwadongs

ahappyeongangmok, possessed in the Jecheon

Memorial Center for Volunteering Army.

In addition to the publication year of the collection, it sometimes provides the completion year of the engraving and also lets us know of any corrections made during the course of engraving. Accordingly, many different kinds of information can be found on the woodblocks.

Engravers worked in groups, and with the names of engravers on the end pieces or on the surfaces, new research on these groups can be conducted. If these studies are linked to a Ganyeoksiilgi (Diary at the time of publication), the information collected could provide important data for further research into unknown aspects of Korean history.

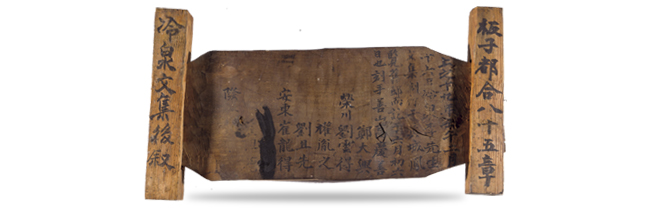

The locations of woodblocks can vary widely between where they were engraved and preserved and their current location, but some woodblocks also contain information about their history, such as the first location where the blocks (Literary Collection of Beonam by Chae Je-gong) was stored. When the history of a set of woodblocks can be confirmed by this information, the past dynamics of a rural community can be revealed. Also, the exact number of woodblocks can be traced by the writing on the woodblocks (Naengcheon Collection of Works by Yi Yu-won).

Information written on the back of a woodblock The place of publication, name and address of engraver, and other information were written on the blank space on the back of the woodblock. Yi Yu-won, Naengcheon Collection of Works.

In particular, the presence of bogwood, used to make corrections, is important. When a mistake is identified, the erroneous character is cut out, and a new character, engraved in bogwood, is inserted. There might be a trace of correcting a wrong character, but sometimes, the trace of corrections hints at much more hidden information. Corrections could involve a single character or one or more lines; sometimes even half of the whole surface could be changed, but the traces of bogwood cannot be detected in the printed collections of works.

Some sensitive issues such as primary sons and secondary sons in a clan, issues capable of causing problems or political concerns, were engraved on woodblocks but excluded in the printed collection. Additionally, information about the whereabouts of some politically divisive figures when the author was alive was frequently removed by the author’s descendants when a collection was republished (Saam True Records by Cheon Man-ri).

With a printed edition, such information can only be confirmed when all of the editions are researched together. However, the woodblocks contain all of this information.

There were also cases where some of the engraved woodblocks were excluded in publishing (Hoedang Literary Collection, Jang Seok-yeong), and where the preface was not published in a printed collection (Poheon Literary Collection, Kwon Deok-su), presumably for political reasons. Sometimes, a new writing was inserted in a printed collection, but the original woodblock was kept. When the volume number of a woodblock and that of the collection are different, the woodblock tells us the author’s family history and some social aspects of that time (Hoedang Literary Collection). On some woodblocks, the term ‘not usable’ was written in ink, and new woodblocks were made, even though printing with the existing ones was possible (Yeonggaji).

Woodblocks also reveal some aspects of the Japanese colonial rule over Korea. Some woodblocks were confiscated and disappeared under the colonial government though their publication records remain. Also, certain facts, sentences or characters were modified or deleted by Japanese authorities. Only woodblocks can prove such a hidden history. If research is conducted on such details, woodblocks could be a source for restoring the hidden history of Korea.

These additional writings and engravings are usually found on the sides of end pieces because they are visible without having to pull out the whole woodblock from a stack or arrangment. Sometimes, this information was written on the bottom side of the end pieces, and other times, it was written on a part of or the whole surface. In this manner, woodblocks give us valuable information such as the names of engravers, orders for corrections, number of volumes and pages and their storage locations, information not verifiable in printed collections of works.