E-mail : master@koreastudy.or.kr

Tel : 82-54-851-0700

The Advanced Center for Korean

Studies copyright ⓒ2014

History of Korean Woodblocks

In a broad sense, a woodblock can refer to any letters or pictures engraved on a wooden plaque. In a narrower sense, it indicates a wooden plate where letters and pictures are carved inversely for the express purpose of printing. Though other wooden items were also engraved with letters or pictures, such as signboards or pillars, this paper will solely discuss wooden printing blocks (hereafter referred to as “woodblocks”).

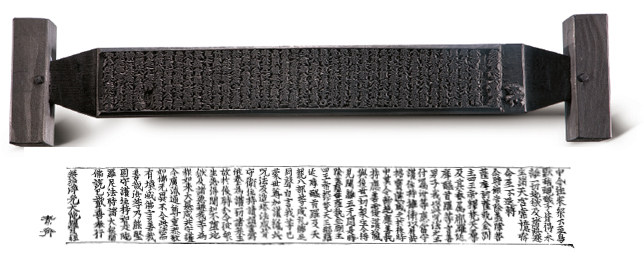

Though it is not known exactly when woodblock printing began in Korea, it is known that woodblock printing originated in China. However, a copy of the Mugujeonggwang Daedaranigyeong (Spotless Pure Light Dharani Sutra), found in a sarira container enshrined in the Seokgatap (Sakyamuni Pagoda) at Bulguksa Temple located in Gyeongju, capital of the Silla Kingdom, was printed in the early or mid-8th century, and is now recognized as the oldest woodblock printing in the world. It demonstrates that Korea already knew about and utilized woodblock printing as early as the Three Kingdoms (4C-668 AD) or Unified Silla (668-935) eras.

of Mugujeonggwang Daedaranigyeong, the oldest wood printing in the world. Reprinted by

Lee Chang-seok, the print master and the 16th intangible cultural asset of Gangwon-do.

Woodblock printing was further developed during the Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392). After its foundation, Goryeo established an organization called “Naeseoseong,” to preserve and manage documents and books, such as important government documents and the Confucian classics. This organization changed its name to “Biseoseong” during the reign of King Seongjong (981-997). With the function of editing and managing governmental documents, Biseoseong supervised publication projects, and all publications were printed using woodblocks form. Later, “Biseogak,” the royal library, was established as the organization to preserve all the books published nationwide. At the same time, the woodblocks necessary for printing were cut and prepared in advance for future publication demands, and woodblock printing became commonplace. Based on its excellent woodblock printing skills, Goryeo published tens of thousands of books, and the Song Dynasty of China dispatched envoys to Goryeo to buy them. During this period, publishing collections of Confucian writings and classics were popular due to the implementation of the Gwageo (Civil Service Examination) and the proliferation of private schools.

In 1234, metal type, the first in the world, was invented to replace woodblock printing. However, woodblock printing did not disappear as engraved wooden plates could preserve records for a long time and depict pictures and maps in detail. Rather, because of the widespread acceptance of Buddhism, demands for woodblock printing grew as it was easier and could depict Buddhist transformational pictures. The epitome of woodblock printing during the Goryeo Dynasty was the Buddhist Tripitaka, and the Goryeo Tripitaka (usually referred to as the “Tripitaka Koreana”) was produced as a state-sponsored project. The first Tripitaka was begun in the 11th century, and a revised Tripitaka was completed in the 13th century. With its vast scope of subject matter and sophisticated engraving technique, the Goryeo Tripitaka was designated a UNESCO Memory of the World in 2007.

Woodblock printing continued to be used during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Printing projects by temples declined as Joseon initially suppressed Buddhism. Later on, however, the demand for Confucian classics and historical books increased drastically as Joseon implemented a policy promoting Confucianism. Accordingly, government-led publishing advanced rapidly using metal type. Interestingly, woodblock printing was still used for books that needed to be distributed or preserved for a long time, while metal type was used for printing important government documents or books. This illustrates the excellent durability and reusability of woodblocks.

Buddhist temples often served as a venue for making woodblocks during the Joseon Dynasty. Originally, the temples had monk engravers. At that time, monks belonged to the lower class and were sometimes tasked to print collections of literary works for the gentry as a form of forced labor. The reasons for this were as follows: temples had engravers, finding and preparing wood for woodblocks around temples was convenient, and temples often manufactured hanji (traditional Korean paper) to offer the government as tribute.

As a way to spread its political ideology, the Joseon Dynasty controlled most publication projects. However, the Sarim (local Confucian scholars) began to enter politics in the 16th century, and the publication of collections of works and genealogies increased slowly for the purpose of boosting their academic legitimacy and family authority. Still, most of the publications were managed by the government.

In the 17th century, provincial administrations were established, and their publications began in earnest. Mainly, books for edification and promulgation were published, and provincial administrator’s individual work collections were printed though the quantity of these was small in comparison.

After the 18th century, academies and family shrines began publishing their own collections of works and genealogies in a competitive manner, and woodblocks emerged as the main printing medium. Later, woodblock printing was also used in the private sector to publish Confucian classics, historical books, and books on etiquette. The increased use of woodblock printing by the private sector was enhanced even further after the late 18th century and reached its peak in the late 19th to early 20th century, accounting for approximately 60 percent of all publications.

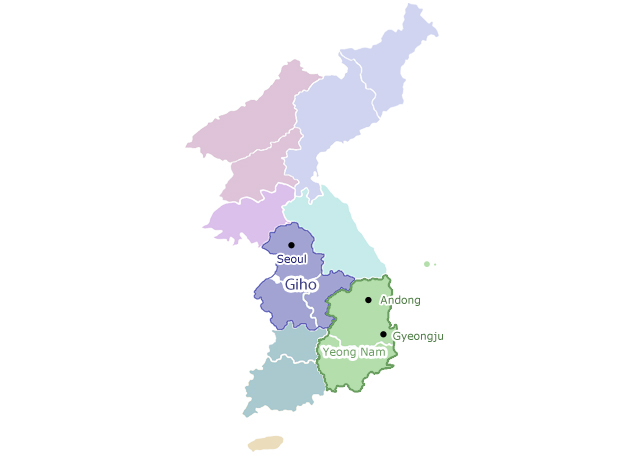

In addition, the Joseon Dynasty witnessed a slow advancement in its economy, which stimulated the use woodblock printing to publish novels for commercial consumption in pursuit of profits. After the Japanese invasion of Joseon in 1592, the Military Training Command published books commercially to pay for operational costs for a while, but it was in the late 17th century when commercially printed novels really took off. Some of these novels specified where it was published, who published it, and other information. Publications included: educational textbooks such as Cheonjamun, Myeongsimbogam, Gomunjinbo, Tonggamjeoryo and various dictionaries; books on rituals such as Saryepyeollam and Garye and novels such as Nine Cloud Dream, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, and Simcheongjeon. These books were mainly published in the Giho area (current Seoul, Gyeonggi and Chungcheong). Since these novels were printed for profit, their sophistication and size were somewhat different from those printed for private collections, though their form was similar.

Seoul. No. 541 of Modern Cultural Property of Korea. Donated by Noh Seung-joo family

from Gyoha Noh Clan. Currently possessed by ACKS.

The Japanese Invasion of 1592 and the Manchu War of 1636 dealt a hard blow to the Joseon economy. Consequently, in the Giho region, printing with wooden type was prevalent over woodblock printing because the former took less time and cost less. In the early 20th century, newly-introduced stone seal printing increased at a remarkable rate. In the Yeongnam region (southeast Korea), however, woodblock printing accounted for most of the book publications, though wooden type and stone seal printings both grew steadily. At that time, the majority of publications were collections of works because the Yeongnam region seemed to have a stronger interest in preserving old literature. This was due to the belief that literary collections preserved the academic achievements of ancient sages and ancestors. While the plates used in moveable type printing are disassembled after printing a book, a woodblock can be used for printing over and over, assuming it is well preserved. Hence, the published collections of works printed using woodblocks were passed down for generations at the academies of ancient sages, regardless of the huge cost of producing woodblocks.

Woodblock printing was developed in East Asia (Korea, China, Japan, Vietnam, etc.), but the Korean process differed from other countries in several importantways:

First, wooden printing blocks were manufactured mainly by academies or clans in Korea, while commercial groups, such as a union of publishers, had their woodblocks made in China and Japan.

Second, wooden printing blocks produced in Korea commemorated the achievements of ancient sages and played a role in concentrating the power and influence of academic cliques in Korea, while in China and Japan woodblock production was mainly in pursuit of commercial profit from publications. Accordingly, the books printed in China and Japan were primarily books used to study for civil service examinations and other popular books. However, books published in Korea during the Joseon period were mainly about Confucianism.

Third, wooden printing blocks produced in Korea had strict deliberation procedures, called public debates, even after the author died. In China and Japan, however, even private collections of works were published when the author was still alive. Accordingly, influences from commercial capital, authors, and others were thoroughly reflected in those books.

In the West, xylography, introduced in the Yuan Dynasty, was popular for a short period of time around the mid-15th century as it was cheaper than metal type. However, with the wide use of metal type, xylography was used more for making woodcuts than for book printing.

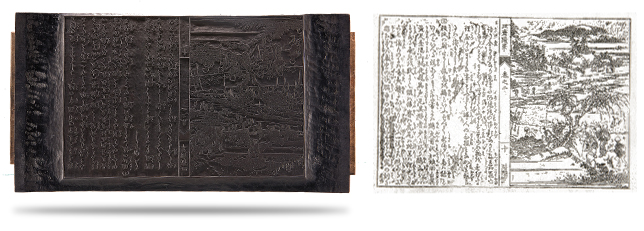

In terms of appearance, the Korean woodblock was different from that of China and Japan. Basically, Korean woodblocks were wider and were equipped with end pieces. In addition, they were engraved on both front and back. However, Chinese and Japanese woodblocks, where commercial publication prevailed, had no end pieces and were relatively thinner. As woodblock printing in Japan was developed via Korea, its form was similar to ancient Korean woodblocks. Furthermore, in Japan, woodblocks were used more to print Buddhist scriptures, whereas in Korea, woodblocks were mainly used for publishing Confucian books.

Ancient Prints at Myeongjusa Temple, Chiaksan Mountain.